I first began to be interested in anthropology some years ago when I was watching a programme on the San tribes of Botswana and Namibia. The presenter of the programme (whose name I have forgotten) jokingly said that the workaholics of the tribe work about 12 hours per week. Or at least did – before the Government encouraged some of them to take up farming and thereafter become consumers.

But we don’t have to go to Botswana or Namibia to illustrate how our work habits have changed! Interestingly, Jürgen Osterhammell in his book The Transformation of the World points out that in Europe, before the Industrial Revolution really got going, (e.g. the mid-1700’s) when almost everyone worked on the land (with little or no labour-saving machinery) ordinary people, over a full year, actually worked less hours per week than when they were working in factories and service industries in the 1900’s.

Over approx. 200 years, as peoples’ disposable income gradually increased, the proportion of it that they spent on necessities like food went down. Engel’s Law also notes this. It states that in the process of industrialisation, (which – it is hoped – has the effect of raising the standard of the poor to that of the middle classes), a country must produce more food with fewer people. But the amount of food needed remains the same. Therefore they spend more on luxuries, which then become necessities.

As society industrialises, people purchase more things, take up outside interests, begin to go on holidays, but then have to work longer to maintain their new lifestyles. We evolved from living in an age of discomfort, need and necessity to an age of comfort, leisure and convenience.

Nowadays, if we’re too cold we turn on the heat, if we’re too warm we turn on the air conditioning. If it’s dark we flick a switch and it’s not dark anymore. If we want to go on holidays in a distant land we hop on a plane, if we want avocados in rainy Ireland we can get them flown in from tropical countries half a world away any time of the year.

We invent things (like the internal combustion engine, plastics, aeroplanes, drugs and medicines, nuclear power, even electricity) that bring us comfort beyond anything our near-ancestors would have dreamed of. Then rather than using the inventions sensibly for life-affirming purposes we use them in a way that ultimately cause harm – with our motives almost always driven by profit alone, such profit being in the hands of a few – not shared equally among the majority of us.

And when, artificially, in communist countries such as the Soviet Union and its satellites, an attempt was made to share profits equally in huge state-controlled businesses it turned out – going on the evidence over many decades of the 20th century – very badly.

One day, just as an exercise, I tried to imagine what it might be like to pare down my life to necessities – or at least the minimum of comforts.

What would life be like to have nothing except what is needed for food and shelter, and to live like someone of modest means in or around the year 1750. I wondered (challenging Jürgen Osterhammell a bit), would going to the well for water instead of turning on a tap, or collecting wood for a fire to boil the water to cook instead of flicking a switch be counted as work? I’m not sure of the above – but I do know after doing the exercise that it is very difficult to imagine a life without modern comforts or conveniences.

The above paragraph implies that the vast majority of us tend to value things more than time and I wondered at the root causes of this preference – because it is undeniable. Is comfort and convenience an illusion?

Which would you prefer?

To work in the fields, every day being different, through times of scarcity and plenty, in the cold and heat of unpredictable nature, vulnerable to diseases and viruses, with simple local food but with little prospects of ever going far from your own village, dependent on a landlord to whom you have to pay rent, and have loads of time off;

Or

Have food supply certain and predictable, have all the comforts of modernity, be able to afford foreign holidays, with chemists and hospitals close by to cure you of any illnesses, for an unchanging wage and have to work 40 hours every week of the year.

Obviously, we prefer the latter – because – through a mixture of our own preferences and the (already described) awesome power of corporate closed-ness – that is what we have chosen!

Nowadays, a substantial proportion of our week is taken up working. And why are we working? It is often far more, in the Western World anyway, about keeping up with the demands of modern society than it is putting food on our tables, clothes on our backs, or a roof over our heads.

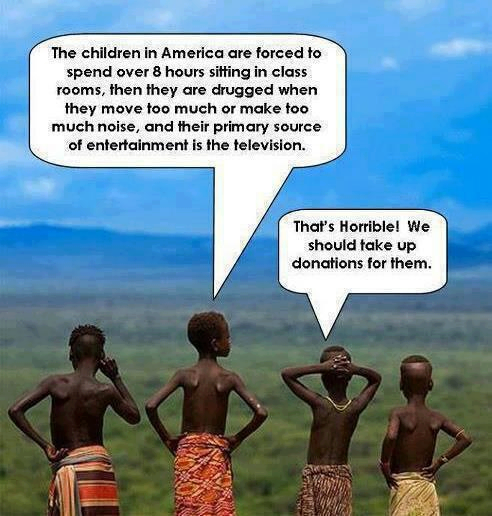

Curious about this, and encouraged by the programme that I saw on the San tribes-people, I began reading about early hunter-gatherer tribes and how they lived in the past and indeed how they are living now. What interested me most is how they managed to sustain what we would describe as a very basic lifestyle over hundreds of generations – and how each generation passed on their values to the next.

Further reading opened my eyes as to how they treat growth and development of children – which I found very interesting (and is one of the reasons why I am including this Chapter). Another reason is that some of the literature concerned how we became conscious of what class we belonged to – and how we began comparing and competing with each other!

In particular, I felt that by way of contrast to how our society is ordered now in the 21st Century and how we tolerate all the things that bother us (corruption, poverty, exploitation and the apparent rising anxiety) but we do nothing about, a short description of how hunter-gatherer tribes live might be of interest.